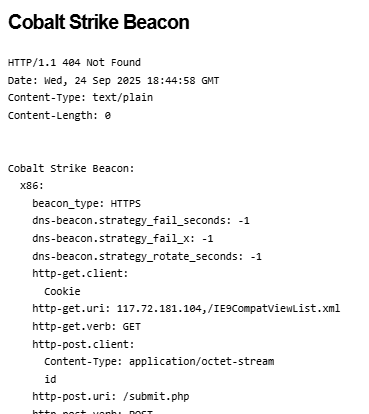

When it comes to attacker infrastructure, some threats are more stealthy than others. Searching “cobalt strike beacon” in Shodan or similar tools can reveal exposed Teams Servers that are not properly protected from the public eye – as shown below.

Additionally, these servers often expose details of configured beacon behavior that can be used to study how attackers are setting up initial payload functionality – an example is shown below.

These types of details are invaluable and allow us to study the settings attackers are using for their Cobalt Strike payloads – often these carry over into other frameworks as well such as Sliver, Mythic, etc. In this post, I present a statistical summary of beacons exposed at the time of this writing to help suggest detection and hunting ideas for blue teams.

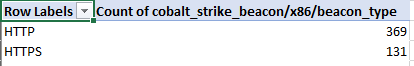

One of the most obvious things we can look at first is understanding the type of beacons that threat actors are using – Cobalt Strike supports a variety of types including HTTP, HTTPS and DNS – threat actors today typically use HTTPS, as evidenced in the below analysis (with DNS being exceedingly rare due to how slow they are to interact with).

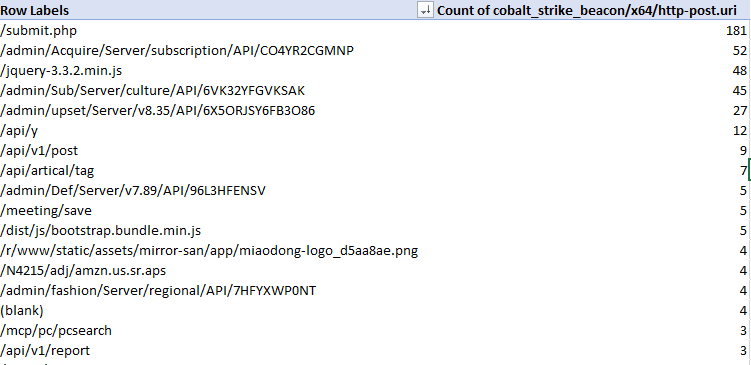

When threat actors are setting up an HTTP-based beacon, they must configure different properties such as the URIs that will be invoked, the user agent, the HTTP verbs, etc – so let’s take a look at these – starting with the most common POST URIs setup by actors.

A couple of these standout – threat actors really like ‘submit.php’, URIs that appear to be API endpoints and URIs that look like common web-app behavior such as loading jquery. This is good material for pivoting using other material to find potential C2 behavior in your network.

Looking at sleeptime also exposes some interesting data – the vast majority of exposed configurations used the default sleeptime setting of 60 seconds – the next biggest bucket of actors reduced this to 3 seconds – then we can observe a variety of different configurations.

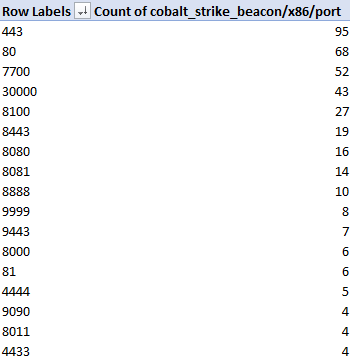

In terms of TCP Ports, we observe beacons communicating on a wide variety of outbound connections. In my experience doing Incident Response, C2 traffic tends to stick to port 80 or 443 but this is evidence that this is not always the case!

The above image shows only the most common ports in use – there were dozens of other ports not pictured that were used by 3 or less observed configurations.

What about the HTTP user agent in use? There was a significant amount of variety here (as expected), with configurations trying to impersonate various browsers and devices such as iPads, Mac OS, Windows, etc. The most commonly observed ones are shown below.

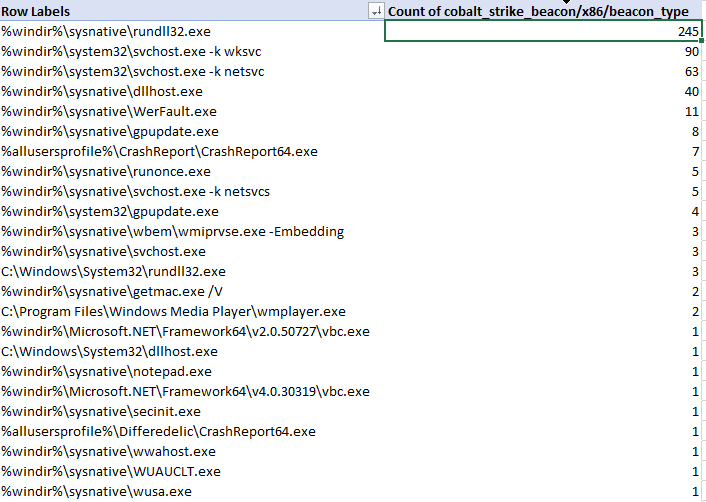

Let’s now analyze the characteristics of beacon process spawning and injection behavior. Cobalt Strike enables operators to configure ‘post exploitation’ configurations that control how sub-processes are spawned from a primary beacon. The table below represents the binaries that were configured for use with post-exploitation tasks such as screenshots, key-logging, scanning, etc.

As we can see, the most common choice by far was rundll32.exe, followed by svchost.exe, dllhost.exe, WerFault.exe and gpuupdate.exe – but there are definitely some less-observed binaries in the table. I would urge defenders to ensure you are considering all possible hunting options when looking for C2 traffic in your network.

There are many additional aspects of Cobalt Strike configurations that we as blue-teamers can pivot and hunt on throughout our networks – the goal of this is to help shine some light on the most commonly used and abused components so that hunt and detection teams can embrace these attributes and improve their security posture. My hope is that you can immediately take some of these data points and action them internally on your own network for finding suspicious activity, should it exist.

I’ll continue this analysis in an additional post as I dive into other C2 servers and additional discovery mechanisms for Cobalt Strike servers, among other platforms.